Asymmetric Numeral Systems

NOTE: trying out a new format (actually really old, from the days of Galileo, see Systema cosmicum). This is a dialogue between three friends Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh who are trying to understand asymmetric numeral systems

The Pre-intro

Vishnu: I have been trying to read the paper Asymmetric Numeral Systems (ANS) by Jarek Duda, but have not made any progress. Have either of you made any progress?

Mahesh: Yeah, it is driving me nuts, only if someone could tell me the TL;DR.

Brahma: Well, I did read it. In fact I have been trying to understand it on-and-off since the past 4-5 years. Seems like I finally understood it. I have still not understood the original paper, but here are some blogs by some fantastic researchers in the area of compression. I found their blogs to be the most useful. Here are links to their write-ups on ANS

- Fabian Giesen: https://fgiesen.wordpress.com/2014/02/02/rans-notes/

- Charles Bloom: https://cbloomrants.blogspot.com/2014/02/02-18-14-understanding-ans-conclusion.html

- Yann Collet: http://fastcompression.blogspot.com/2013/12/finite-state-entropy-new-breed-of.html

I would recommend starting with Fabian's blog. He talks specifically about rANS, which is one of the many variants of compressors introduced by Jarek. I found the specificity simpler to start with.

All the best! I have to now go and meditate.

Mahesh: Well hold on! I will look at these links in detail, but can you maybe give a short intro?

Brahma: Hmm, alright! The ANS paper introduces a set of new compression algorithms, namely the rANS (range-ANS) and tANS (table-ANS) compression algorithm. To be more precise rANS and tANS are actually a family of compression methods which provide a good tradeoff between compression and speed.

I found it is easier to start with rANS and then develop tANS as a consequence of optimizations under certain parameter regimes. This is in-fact the path which Fabian and Charles choose in their blogs, Yann chooses the reverse path of directly tackling tANS, which is also interesting in itself!

Vishnu: Sounds good! But even before we go there, can you explain why the name of the paper: Asymmetric Numeral Systems?

The Introduction

Brahma: Okay, lets start the story from the beginning:

Lets say the problem is that we are given a sequence of digits in [0,9], and we want to represent them with a single number x.

Lets say we are given the sequence 3,2,4,1,5. Then how can we form a single number representing them?

Vishnu: Umm, isn't this trivial? If we are given digits 3,2,4,1,5, I can just form the number x = 32415

Brahma: Thats right! this is what we do everyday in our lives. Lets however try to understand what we just did in a different way. What we are actually doing is the following: We are starting with the state x = 0, and then updating it as we see each symbol:

x = 0 # <-- initial state

x = x*10 + 3 # x = 3

x = x*10 + 2 # x = 32

...

x = x*10 + 5 # x = 32415

Thus, during the encoding we are start with state x=0, and then it increases as x = 0, 3, 32, 324, 3214, 32145 as we encode the symbols.

Can either of you tell me how would you decode back the sequence if I give you the final state 32145?

Mahesh: Sure, then we can decode the sequence as:

symbols = []

x = 32145 # <- final state

# repeat 5 times

s, x = x%10, x//10 # s,x = 5, 3214

symbols.append(s)

at the end, you would get symbols = [5,4,1,2,3].. which would need to be reversed to get your input sequence.

Brahma: Precisely! Notice that during the decoding, we are just reversing the operations, i.e: the encode_step and decode_step are exact inverses of each other. Thus, the state sequence we see is 32145, 3214, 321, ..., 3 is the same as during encoding, but in the reverse order.

def encode_step(x,s):

x = x*10 + s

return x

def decode_step(x)

s = x%10 # <- decode symbol

x = x//10 # <- retrieve the previous state

return (s,x)

We have until now spoken about representing an input sequence of digits using a single state x. But how can we turn this into a compressor? We need a way to represent the final state x using bits.

Mahesh: That is again quite simple: we can just represent x in binary using ceil(log_2[x])) bits. For example in this case:

32145 = 111110110010001. Our "encoder/decoder" can be written as:

## Encoding

def encode_step(x,s):

x = x*10 + s

return x

def encode(symbols):

x = 0 # initial state

for s in symbols:

x = encode_step(x,s)

return to_binary(x)

## Decoding

def decode_step(x):

s = x%10 # <- decode symbol

x = x//10 # <- retrieve the previous state

return (s,x)

def decode(bits, num_symbols):

x = to_uint(bits) # convert bits to final state

# main decoding loop

symbols = []

for _ in range(num_symbols):

s, x = decode_step(x)

symbols.append(s)

return reverse(symbols) # need to reverse to get original sequence

Brahma: Thats right Mahesh! Can you also comment on how well your "compressor" is compressing data?

Mahesh:: Let me see: if we look at the encode_step, we are increasing it by a factor of 10 x_next <- 10*x. There is the small added symbol s, but it is quite small, compared to the state x after some time. As we use ~ log_2(x) bits to represent the state. Increasing it 10 times, we are using ~log_2(10) bits per symbol.

Vishnu: I see! So, we are effectively using around log_2(10) bits per symbol. I think that is optimal if all our digits [0,9] are equiprobable and have probability 1/10 each. But, what if the symbols are not equi-probable? I think in that case this "compressor" might do a bad job.

Brahma: Good observation Vishnu! That is precisely correct. One thumb-rule we know from Information theory is that if a symbol occurs more frequently, it should use less bits than the symbol which occurs less frequently. In fact, we know that on average a symbol s with probability prob[s] should optimally use log_2 (1/prob[s]) bits.

Let me even put this thumb-rule in a box to emphasize:

avg. optimal bits for a symbol s = log_2 (1/prob[s])

Notice that our compressor is using log_2(10) = log_2(1/10), which validates the fact that our compressor is optimal if our symbols have probability 1/10, but otherwise it is not.

Vishnu: Thats a very useful thumb rule. I think our compressor will be "fixed" if the encode_step increases the state x as:

x_next ~ x* (1/prob[s]). In that case, effectively our symbol s is using log_2(1/prob[s]) bits.

Brahma: Very good Vishnu! You have got the correct intuition here. In fact this is the core idea behind rANS encoding. Ohh, to answer Mahesh's question: what we were doing with our "compressor" was our usual Symmetric Numeral System, where the probability of all symbols is the same. We will now be discussing the Asymmetric Numeral Systems which will handle the case where the digits don't have the same probability.

Mahesh: Ahh, cool! I now understand the title of the paper :)

Theoretical rANS

Brahma: Okay, before we go into the details of rANS, lets define some notation: as x is an integer, lets represent prob[s] using rational numbers:

prob[s] = freq[s]/M

where M = freq[0] + freq[1] + ... + freq[9], i.e. the sum of frequencies of all symbols (also called as Range Factor). Here freq[s] is also called the "Frequency" of symbol s. Lets also define cumul[s], the cumulative frequency. i.e:

cumul[0] = 0

cumul[1] = freq[0]

cumul[2] = freq[0] + freq[1]

...

cumul[9] = freq[0] + freq[1] + ... + freq[8]

For example: if we limit ourselves to only the digits {0,1,2}:

freq -> [3,3,2], M = 8

cumul -> [0,3,6]

prob -> [3/8, 3/8, 2/8]

Is this setting clear?

Vishnu: Yes, yes, basically you are just representing everything with integers. Lets go ahead!

Brahma: Haha allright! Okay, so the rANS encoding follows the exact same pattern we saw earlier. i.e.

We still start from state x=0 and then update the state every time we see a new symbol. The main difference is that our encode_step doesn't just do x*10 + s; we do something slightly more intricate here:

## Encoding

def rans_base_encode_step(x,s):

# add details here

return x

def encode(symbols):

x = 0 # initial state

for s in symbols:

x = rans_base_encode_step(x,s)

return to_binary(x)

Any guesses on what the rans_base_encode_step(x,s) should be?

Mahesh: I think based on our discussion earlier, for optimal compression we want the state x to roughly increase as x_next <- x/prob[s]. Thus, in the notation you defined, I would say there has to be a term something similar to:

x_next ~ (x//freq[s])*M

Brahma: Very good Mahesh! In fact the true rans_base_encode_step is quite close to what you suggested, and is as follows:

## Encoding

def rans_base_encode_step(x,s):

x_next = (x//freq[s])*M + cumul[s] + x%freq[s]

return x_next

Lets take a concrete example: If we consider our example distribution:

symbols = [0,1,2]

freq -> [3,3,2], M = 8

cumul -> [0,3,6]

and the sample input as [1,0,2,1], then the encoding proceeds as follows:

step 0: x = 0

step 1: s = 1 -> x = (0//3)*8 + 3 + (0%3) = 3

step 2: s = 0 -> x = (3//3)*8 + 0 + (3%3) = 8

step 3: s = 2 -> x = (8//2)*8 + 6 + (8%2) = 38

step 4: s = 1 -> x = (38//3)*8 + 3 + (38%3) = 101

Any observations?

Vishnu: One thing I noticed is that, if we choose the uniform probability scenario where prob[s] = 1/10, for s in [0,9] i.e. freq[s] = 1, M = 10, then we reduce to the symmetric numeral system formula!

# rANS state update

x_next = (x//freq[s])*M + cumul[s] + x%freq[s]

# substitute freq[s] = 1, M = 10

x_next = x*10 + s

Brahma: Indeed! We reduce to the symmetric numeral system, if all the probabilities are equal; which is good news!

Okay, now that we have understood the encoding, lets try to understand the decoding. The decoding also proceeds in a similar fashion: we start with the final state x and in each step try to decode the symbol and the previous state.

def rans_base_decode_step(x):

# perform decoding

return (s,x_prev)

def decode(bits, num_symbols):

x = to_uint(bits) # convert bits to final state

# main decoding loop

symbols = []

for _ in range(num_symbols):

s, x = rans_base_decode_step(x)

symbols.append(s)

return reverse(symbols) # need to reverse to get original sequence

Any thoughts on how the decoding might proceed?

Mahesh: Let me give it a shot: Essentially we just want to find the inverse of the rans_base_encode_step right?

So let me start by writing that down:

x = (x_prev//freq[s])*M + cumul[s] + (x_prev % freq[s])

Given x we want to retrieve the symbol s and x_prev... but, I am not sure how to make progress (:-|)

Brahma: Good start Mahesh. Let me give you a hint, we can write the encoding step as follows:

block_id = x_prev//freq[s]

slot = cumul[s] + (x_prev % freq[s])

x = block_id*M + slot

One thing to notice is that 0 <= slot < M, as:

slot = cumul[s] + (x_prev % freq[s])

< cumul[s] + freq[s]

<= M

Does this help?

Mahesh: Aha! yes, I think as 0 <= slot < M, one can think of it as the remainder on dividing x with M. So, I can retrieve the block_id and slot as:

# encode step

x = block_id*M + slot

# decode step:

block_id = (x//M)

slot = (x%M)

Brahma: Good job Mahesh! That is a good first step. Vishnu, can you go ahead and retrieve s, x_prev from slot, block_id?

Vishnu: We know that 0 <= slot < M. But we know a bit more about the slot:

slot = cumul[s] + (x_prev % freq[s])

< cumul[s] + freq[s]

= cumul[s+1]

i.e.

cumul[s] <= slot < cumul[s+1]

So, once we obtain the slot, we can just do a linear/binary search over the list [cumul[0], cumul[1], ... cumul[9], M] to decode s.

Once we have decoded the symbol s, we know freq[s], cumul[s]. So, we can decode x_prev as:

x_prev = block_id*freq[s] + slot - cumul[s]

Thus, the decoding can be described as follows:

def rans_base_decode_step(x):

# Step I: find block_id, slot

block_id = x//M

slot = x%M

# Step II: Find symbol s

s = find_bin(cumul_array, slot)

# Step III: retrieve x_prev

x_prev = block_id*freq[s] + slot - cumul[s]

return (s,x_prev)

Brahma: Absolutely correct Vishnu! That is very precise. So that we all are on the same page, lets again go through our example:

symbols = [0,1,2]

freq -> [3,3,2], M = 8

cumul -> [0,3,6]

and the sample input as [1,0,2,1] -> final state x = 101

Lets see how the decoding goes:

x = 101

# Step I

block_id = 101//8 = 12

slot = 101%8 = 5

# Step II

cumul_array = [0, 3, 6, 8]

as 3 <= slot < 6, the decoded symbol s=1

# Step III

x_prev = 12*3 + 5 - 3

x_prev = 38

Voila! we have thus decoded s=1, x_prev=38. We can now continue to decode other symbols. To summarize, here are our full encode decode functions:

####### Encoding ###########

def rans_base_encode_step(x,s):

x_next = (x//freq[s])*M + cumul[s] + x%freq[s]

return x_next

def encode(symbols):

x = 0 # initial state

for s in symbols:

x = rans_base_encode_step(x,s)

return to_binary(x)

####### Decoding ###########

def rans_base_decode_step(x):

# Step I: find block_id, slot

block_id = x//M

slot = x%M

# Step II: Find symbol s

s = find_bin(cumul_array, slot)

# Step III: retrieve x_prev

x_prev = block_id*freq[s] + slot - cumul[s]

return (s,x_prev)

def decode(bits, num_symbols):

x = to_uint(bits) # convert bits to final state

# main decoding loop

symbols = []

for _ in range(num_symbols):

s, x = rans_base_decode_step(x)

symbols.append(s)

return reverse(symbols) # need to reverse to get original sequence

Mahesh: Great! I think, I now understand the rANS base encoding and decoding step quite well. Essentially, we are increasing the state by approximately x_next ~ x/prob[s] as needed to be optimal, but we are doing it in a smart way, so that we can follow our steps backwards and retrieve the encoded symbols and state.

One think I noticed is that, as the state is growing by a factor of ~ 1/prob[s] at every step.. it is growing exponentially, and practically would surpass the 64-bit (or 32-bit) limit on computers. So, I think that is the reason you are calling this theoretical rANS. I think there is still some work left to make this algorithm practical.

Brahma: Yes, that is correct Mahesh; the state x does increase exponentially. For example, in our example it increases as 0, 3, 8, 38, 101, .... Thus we need to somehow limit the state from growing beyond a certain limit. That is however a story for some other day. Let me leave you both here to re-think the base rANS steps!

Mahesh, Vishnu: Thank you Brahma! See you next time!

Streaming rANS

Brahma: Okay, hope you guys had time to revise on the base rANS step. Lets now talk about how to make it practical. As you recall, every time we call the the x = rans_base_encode_step(x,s), we are typically increasing the state x exponentially. Thus, we need some way to limit this growth.

The methodology employed by Jarek Duda in his paper is ingenious, but at the same time quite simple. The goal is to limit the state x to always lie in a pre-defined range [L,H].

Mahesh: Even before we go into the details, I have a fundamental question: as a final step of rANS, we represent state x using ceil(log_2(x)) bits. However, if x is always going to lie in the range [L,H], we can at maximum transmit ceil(log_2(H)) bits of information, which doesn't seem much.

Brahma: Sharp observation Mahesh. In the theoretical rANS discussion, the only bits we write out are at the end, and are equal to ceil(log_2(x)). It is clear that this is not going to work if x is not growing. So, in the streaming rANS case, along with writing out the final state at the end, we stream out a few bits after we encode every symbol. Thus, the new encoding structure looks like this:

def encode_step(x,s):

# update state + output a few bits

return x_next, out_bits

def encode(symbols):

x = L # initial state

encoded_bitarray = BitArray()

for s in symbols:

x, out_bits = encode_step(x,s)

# note that after the encode step, x lies in the interval [L,H]

assert x in Interval[L,H]

# add out_bits to output

encoded_bitarray.prepend(out_bits)

# add the final state at the beginning

num_state_bits = ceil(log2(H))

encoded_bitarray.prepend(to_binary(x, num_state_bits))

return encoded_bitarray

As you can see, the new encode_step doesn't just update the state x, but it also outputs a few bits.

Vishnu: Cool! That makes sense. I have a couple of observations:

-

I see that the initial state in

streaming rANSisx = Land notx = 0. I also see you have anassert x in Interval[L,H]after theencode_step. So, it seems that the input state toencode_stepand its output always lie inInterval[L,H]. -

Another interesting I noticed is that you prepend

out_bitsto the finalencoded_bitarray. I am guessing this is because therANSdecoding decodes symbols in the reverse order right?

Brahma: That is right Vishnu! similar to rANS decoding, the streaming rANS decoder also proceeds in the reverse direction, and hence needs to access the bits in the reversed order. (NOTE: prepending could be a bit tricky and slow, due to repeated memory allocations.. but lets worry about the speed later!)

Lets now take a look at the decoder structure in case of streaming rANS:

def decode_step(x, enc_bitarray):

# decode s, retrieve prev state

# also return the number of bits read from enc

return s, x_prev, num_bits_step

def decode(encoded_bitarray, num_symbols):

# initialize counter of bits read from the encoded_bitarray

num_bits_read = 0

# read the final state

num_state_bits = ceil(log2(H))

x = to_uint(encoded_bitarray[:num_state_bits])

num_bits_read += num_state_bits

# main decoding loop

symbols = []

for _ in range(num_symbols):

# decoding step

s, x, num_bits_step = decode_step(x, encoded_bitarray[num_bits_read:])

symbols.append(s)

# update num_bits_read counter

num_bits_read += num_bits_step

return reverse(symbols) # need to reverse to get original sequence

The decoder starts by retrieving the final state by reading num_state_bits bits from the encoded_bitarray. Once it has retrieved the final state x, we call the decode_step function in a loop until we have decoded all the symbols, as in case of rANS. The difference now is that the decode_step function also consumes a few bits (num_bits_step). As you can imagine, these num_bits_step correspond to the length of the out_bits from the encode_step.

Mahesh: I see! This makes sense. So, now the missing component in our algorithms are the encode_step and decode_step functions, which need to be perfect inverses of each other, but at the same time need to ensure that the state x lies in the Interval[L,H].

Brahma: Thats right Mahesh! Lets think about the encode_step first. Let me start by writing its structure, so that we understand how we are modifying the basic rans_base_encode_step:

def shrink_state(x,s):

# TODO

# reduce the state x -> x_shrunk

return x_shrunk, out_bits

def encode_step(x,s):

# shrink state x before calling base encode

x_shrunk, out_bits = shrink_state(x, s)

# perform the base encoding step

x_next = rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s)

return x_next, out_bits

Any thoughts Vishnu?

Vishnu: Hmm, lets look at the encode_step function. We still have the rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s) call as before; but before this base encode step, we seem to modify the state x -> x_shrunk using the shrink_state(x,s) function call, which as the name suggests is probably making the state smaller.

I think I understand intuitively what is happening: We know that the input state x to encode_step lies in the range [L,H]. We also know that typically rans_base_encode_step increases the state; Thus, to ensure x_next lies in [L,H], we shrink x -> x_shrunk beforehand.

Brahma: Thats right! The main function of shrink_state is indeed to reduce the state x -> x_shrunk, so that after encoding symbol s using the rans_base_encode_step, the output state, x_next lies in [L,H].

One more thing to note is that, as we are performing lossless compression, the "information" content should be retained at every step. If we look at the encode_step function, and the two sub-steps:

- We know that

rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s)encodes the information of the statesand statex_shrunkinto a single statex_next, and that no information is lost. - Thus, the first step

shrink_statealso needs to also ensure that statexis retrievable fromx_shrunkandout_bits.

As we will see, the shrink_state function basically tries to do this, in the simplest possible way:

def shrink_state(x,s):

# initialize the output bitarray

out_bits = BitArray()

# shrink state until we are sure the encoded state will lie in the correct interval

while rans_base_encode_step(x,s) not in Interval[L,H]:

out_bits.prepend(x%2)

x = x//2

x_shrunk = x

return x_shrunk, out_bits

The shrink_state function shrinks the state by streaming out the lower bits of the state x. For example, if state x = 22 = 10110b, then then shrink_state could output:

# input state

x = 21 = 10110b

# output options:

x_shrunk = 10110b = 22, out_bits = ""

x_shrunk = 1011b = 11, out_bits = "0"

x_shrunk = 101b = 5, out_bits = "10"

x_shrunk = 10b = 2, out_bits = "110"

...

The question is now: how many bits to stream out from x?

the answer is quite simple; as we want to ensure that

rans_base_encode_step(x,s) lies in Interval[L,H], we keep streaming out bits until this condition is satisfied! It is quite simple in the hindsight.

Any thoughts Vishnu?

Vishnu: Yes, I think it is quite simple and intuitive. I however think that we have to choose the Interval [L,H] carefully, as otherwise it might be possible that there is no state x_shrunk for which rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s) is in that interval.

Brahma: That is right Vishnu, the range will have to be chosen carefully and precisely. We will also see that we can simplify the comparison step while rans_base_encode_step(x,s) not in Interval[L,H], so that we don't need to call the base_encode_step multiple times. But, before that, lets see if we can understand how the decode_step might work. Any thoughts on the same Mahesh?

Mahesh: Let me start by thinking about the overall decode_step structure first. I think as the decode_step has to be an inverse of encode_step, we need to have expand_state step which is an inverse of the shrink_state step. Also, as the decoding proceeds in a reverse order: so, we first perform the rans_base_decode_step and then call the expand_state function.

def expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray):

# TODO

# read in bits to expand x_shrunk -> x

return x, num_bits_step

def decode_step(x, enc_bitarray):

# decode s, retrieve prev state

s, x_shrunk = rans_base_decode_step(x)

# expand back x_shrunk to lie in Interval[L,H]

x_prev, num_bits_step = expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray)

return s, x_prev, num_bits_step

Brahma: Thats good Mahesh! Another way to intuitively think about expand_state is that: typically rans_base_decode_step reduces the state value, so we need to expand it back using expand_state function so that it lies back in the range [L,H]. Any thoughts on the specifics of expand_state function?

Mahesh: Sure, let me think! We basically want to do the inverse of what we do in the shrink_state function.

We know that the input state x to the shrink_state(x,s) lies in x in Interval[L,H], so in the expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray), we can read in the bits into the state x_shrunk, until it lies in Interval[L,H]. Thus, the expand_state function might look like:

def expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray):

# init

num_bits_step = 0

# read in bits to expand x_shrunk -> x

x = x_shrunk

while x not in Interval[L,H]:

x = x*2 + enc_bitarray[num_bits_step]

num_bits_step += 1

return x, num_bits_step

Brahma: Good job Mahesh, your expand_state function is very precise! However, as Vishnu said in case of encode_step, one thing to note even in case of the decoding is that, we need to choose the L and H values carefully.

For example: we need to make sure that while we expand the state as: x = x*2 + enc_bitarray[num_bits_step], there is a unique x which lies in the Interval[L,H], as otherwise there is no guarantee that the the state x we obtain from expand_state function is the same as the one which the shrink_state function used as input.

Choosing the Interval[L,H]

Brahma: Okay, lets try to answer the final piece of the streaming rANS puzzle: the choice of the values L, H. Instead of trying to derive all possible values for L,H, I am going to straightaway present the solution given by Duda in his paper, and we will try to understand why that works:

The acceptable values for L, H for streaming rANS are:

L = M*t

H = 2*M*t - 1

where M = freq[0] + freq[1] + ... + freq[9] (sum of frequencies), and t is an arbitrary unsigned integer. Any thoughts?

Vishnu: Okay, lets see: Based on the previous discussions, the two conditions we need the Interval[L,H] to satisfy are:

1: encode-step-constraint: The shrink_state function can be understood in terms of the shrinking operation:

start -> x_0 in Interval[L,H]

shrink_op -> x_i = x_{i-1}//2

Then, Interval[L,H] should be large enough so that for all x_0 in Interval[L,H], there is at least one i such that rans_base_encode_step(x_i,s) in Interval[L,H] for all symbols s

2: decode-step-constraint: During the expand_state we repeatedly perform the state expansion operation:

start -> x_0

expand_op -> x_i = 2*x_{i-1} + bit

The Interval[L,H] should be small enough so that there is at max a single i for which x_i in Interval[L,H].

I think it is easy to see that the second constraint, i.e. decode-step-constraint will be satisfied if we choose L, H as: L, H <= 2L - 1. The idea is simple.. Lets assume that x_{i-1} in interval[L,H, i.e x_{i-1} >= L. Then x_i = 2*x_{i-1} + bit >= 2*L > H. Thus, if x_{i-1} is in the Interval[L,H], then x_{i} cannot. Thus if H <= 2L - 1, then the decode-step-constraint is satisfied.

I am not sure how to ensure the first constraint is satisfied.

Brahma: Good job Vishnu with the second constraint. As for the first constraint, the encode-step-constraint: lets start by writing down rans_base_encode_step:

def rans_base_encode_step(x,s):

x_next = (x//freq[s])*M + cumul[s] + x%freq[s]

return x_next

Now, for any given symbol s, it is clear that rans_base_encode_step(x, s) is monotonically increasing in x. If not, I will leave it as an exercise for you to verify!

Now, lets see what range of values of x_shrunk map to in the Interval[L,H], where L = M*t, H = 2*M*t - 1:

M*t = rans_base_encode_step(freq[s]*t,s)

2*M*t = rans_base_encode_step(2*freq[s]*t,s)

Thus, as rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk, s) is monotically increasing, if freq[s]*t <= x_shrunk <= (2*freq[s] - 1), only then

rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk, s) in Interval[L,H].

So, to satisfy the encode-step-constraint, we need to argue that, as we remove bits from x_shrunk, it will always end up in the Interval[freq[s]*t, 2*freq[s]*t - 1]. This is again true for a similar argument as to what we discussed for decode-step-constraint. (I will again keep it an exercise for you to prove this!).

So, we can conclude that:

For streaming rANS: L=Mt, H=2M*t - 1

Vishnu: Wow, that was a bit involved, but I now understand how the L, H values were chosen by Duda! Essentially everything revolves around the interval of type [l, 2*l-1]. These intervals play well with the shrinking op (i.e x -> x//2) or the expand op (x -> x*2 + bit), and guarantee uniqueness.

Mahesh: Yeah, that was quite innovative of Duda! Another thing which I noticed from Brahma's arguments is that:

we can basically replace the check while rans_base_encode_step(x,s) not in Interval[L,H] with while x not in Interval[freq[s]*t, 2*freq[s]*t - 1]. That way, we don't need to call the rans_base_encode_step again and again, and this should increase our encoding efficiency.

Brahma: Good observation Mahesh! And, in fact that was the last thing we needed to complete our streaming rANS. To summarise here are our full encoder and decoder:

########################### Global variables ############################

freq[s] # frequencies of symbols

cumul[s] # cumulative frequencies of symbols

M = freq[0] + freq[1] + ... + freq[9] # sum of all frequencies

## streaming params

t = 1 # can be any uint

L = M*t

H = 2*M*t - 1

########################### Streaming rANS Encoder ###########################

def rans_base_encode_step(x,s):

x_next = (x//freq[s])*M + cumul[s] + x%freq[s]

return x_next

def shrink_state(x,s):

# initialize the output bitarray

out_bits = BitArray()

# shrink state until we are sure the encoded state will lie in the correct interval

while rans_base_encode_step(x,s) not in Interval[freq[s]*t,2*freq[s]*t - 1]:

out_bits.prepend(x%2)

x = x//2

x_shrunk = x

return x_shrunk, out_bits

def encode_step(x,s):

# shrink state x before calling base encode

x_shrunk, out_bits = shrink_state(x, s)

# perform the base encoding step

x_next = rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s)

return x_next, out_bits

def encode(symbols):

x = L # initial state

encoded_bitarray = BitArray()

for s in symbols:

x, out_bits = encode_step(x,s)

# note that after the encode step, x lies in the interval [L,H]

assert x in Interval[L,H]

# add out_bits to output

encoded_bitarray.prepend(out_bits)

# add the final state at the beginning

num_state_bits = ceil(log2(H))

encoded_bitarray.prepend(to_binary(x, num_state_bits))

return encoded_bitarray

########################### Streaming rANS Decoder ###########################

def rans_base_decode_step(x):

# Step I: find block_id, slot

block_id = x//M

slot = x%M

# Step II: Find symbol s

s = find_bin(cumul_array, slot)

# Step III: retrieve x_prev

x_prev = block_id*freq[s] + slot - cumul[s]

return (s,x_prev)

def expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray):

# init

num_bits_step = 0

# read in bits to expand x_shrunk -> x

x = x_shrunk

while x not in Interval[L,H]:

x = x*2 + enc_bitarray[num_bits_step]

num_bits_step += 1

return x, num_bits_step

def decode_step(x, enc_bitarray):

# decode s, retrieve prev state

s, x_shrunk = rans_base_decode_step(x)

# expand back x_shrunk to lie in Interval[L,H]

x_prev, num_bits_step = expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray)

return s, x_prev, num_bits_step

def decode(encoded_bitarray, num_symbols):

# initialize counter of bits read from the encoded_bitarray

num_bits_read = 0

# read the final state

num_state_bits = ceil(log2(H))

x = to_uint(encoded_bitarray[:num_state_bits])

num_bits_read += num_state_bits

# main decoding loop

symbols = []

for _ in range(num_symbols):

# decoding step

s, x, num_bits_step = decode_step(x, encoded_bitarray[:num_bits_read])

symbols.append(s)

# update num_bits_read counter

num_bits_read += num_bits_step

return reverse(symbols) # need to reverse to get original sequence

Whoosh! That concludes our discussion of making rANS practical. You should now be able to take this pseudocode and implement a working rANS compressor. There are some optimizations + parameter choices we can perform on streaming rANS, to make it even better. However, I will leave that discussion for some other time. Now I have to go back to meditating! The Asymmetric Numeral Systems story is not over yet...!

Vishnu, Mahesh: Thanks Brahma! That was a great discussion. Lets take a few days to ruminate over this.. we will be back to finish the story!

rANS in practice

Brahma: Allright! Now that we have understood the Streaming rANS algorithm, lets try to understand the speed of the algorithm, and see what all modifications we can do to make the encoding/decoding faster.

Lets start with the parameter choices. One of the most fundamental parameters is M = sum of freqs. As a reminder, given the input probability distribution, prob[s], we chose the values freq[s] and M so that:

prob[s] ~ freq[s]/M

Any thoughts on how the choice of M impacts the rANS algorithm?

Vishnu: I think as for the compression performance is concerned, we probably want M as high as possible so that the approximation prob[s] ~ freq[s]/M is good. As for speed: lets' take a re-look at rans_base_encode_step and rans_base_decode_step:

def rans_base_encode_step(x,s):

x_next = (x//freq[s])*M + cumul[s] + x%freq[s]

return x_next

def rans_base_decode_step(x):

# Step I: find block_id, slot

block_id = x//M

slot = x%M

# Step II: Find symbol s

s = find_bin(cumul_array, slot)

# Step III: retrieve x_prev

x_prev = block_id*freq[s] + slot - cumul[s]

return (s,x_prev)

If we look at the rans_base_encode_step, we have a multiplication with M ( x_next = (x//freq[s])*M + ...). Choosing M to be a power of 2 will make this multiplication a bit-shift and slightly speed up the encoding.

Also, if we look at the rans_base_decode_step, we have operations such as

# Step I: find block_id, slot

block_id = x//M

slot = x%M

I think both of these operations should be faster if M = 2^r for some r.

Brahma: Thats a good observation Vishnu. Indeed in practice, M is chosen to be of the form M=2^r, typically M = 2^{16} or higher for sufficient precision.

M = 2^r i.e. M is typically chosen to be a power of 2

Vishnu: I however noticed that even after the M=2^r change, the rans_base_encode_step is still probably slow because of the division by freq[s] (x_next = (x//freq[s])*M + ...).

Also, rans_base_decode_step seems to be dominated by the binary search over the cumul[s] array:

# Step II: Find symbol s

s = find_bin(cumul_array, slot)

Any idea if we can speed this up?

Brahma: Good observations Vishnu! Indeed we need to address these bottlenecks. As far as the rans_base_encode_step is concerned the division by freq[s] can be sped up a bit by pre-processing reciprocals 1/freq[s] and multiplying by them. Check out the nice blog by Fabian Giesen on the same: on the same.

As far as the find_bin step is concerned, unfortunately there is no simple way to make it fast, without changing the rANS algorithm itself! This is again mentioned in the blog link by Fabian, in a modification which he refers to as the alias method.

I will leave it as an exercise for you to look through the details of the alias method. The end result is however that instead of taking log(alphabet size) comparisons for the binary search, we now only need a single comparison during the base decoding. This however leads to making the base encoding a bit slower, essentially shifting the compute from encoding to decoding!

Vishnu: Wow! definitely sounds interesting.

Mahesh: Thanks Brahma! It is nice to see tricks to speed up the rans_base_encoding/decoding steps. I however wonder if we have been giving too much emphasis on speeding the base steps. The encoding for example also includes the shrink_state state, which we haven't thought about. Maybe we should look into how to speed those up?

Brahma: That is right Mahesh, we can do a few things to speed up shrink_state and expand_state functions. Let me start by writing them down again:

# [L,H] -> range in which the state lies

L = M*t

H = 2*L - 1

def shrink_state(x,s):

# initialize the output bitarray

out_bits = BitArray()

# shrink state until we are sure the encoded state will lie in the correct interval

while rans_base_encode_step(x,s) not in Interval[freq[s]*t,2*freq[s]*t - 1]:

out_bits.prepend(x%2)

x = x//2

x_shrunk = x

return x_shrunk, out_bits

def expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray):

# init

num_bits_step = 0

# read in bits to expand x_shrunk -> x

x = x_shrunk

while x not in Interval[L,H]:

x = x*2 + enc_bitarray[num_bits_step]

return x, num_bits_step

If you notice, in both shrink_state and expand_state, we are streaming out/in 1 bit at a time. Due to the memory layout on modern computer architectures where the memoery unit is of size 32-bits/64-bits, this might be slower than say accessing a byte at a time.

Any thoughts on how we can modify the algorithm to read/write more than one bit at a time?

Mahesh: I think i got this! If you recall, our choice of range H=2*L - 1, was chosen mainly because we are reading in/out one bit at a time. If we choose, H = 256*L - 1 for example, I think we should be able to write 8 bits at a time, and still guarantee everything works out fine.

The new shrink_state and expand_state would then be:

# [L,H] -> range in which the state lies

b = 8 # for example

b_factor = (1 << NUM_OUT_BITS) # 2^NUM_OUT_BITS

L = M*t

H = b_factor*L - 1

def shrink_state(x,s):

# initialize the output bitarray

out_bits = BitArray()

# shrink state until we are sure the encoded state will lie in the correct interval

x_shrunk = x

while rans_base_encode_step(x,s) not in Interval[freq[s]*t,b_factor*freq[s]*t - 1]:

out_bits.prepend(x%b_factor)

x = x//b_factor

x_shrunk = x

return x_shrunk, out_bits

def expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray):

# init

num_bits_step = 0

# read in bits to expand x_shrunk -> x

x = x_shrunk

while x not in Interval[L,H]:

x = x*b_factor + to_uint(enc_bitarray[num_bits_step:num_bits_step+b])

num_bits_step += b

return x, num_bits_step

I think that should satisfy the constraints we had laid out for the strink_state and expand_state functions, but allow us to stream out b bits at a time.

Brahma: Very good Mahesh! The code indeed gets a bit complicated, but this does lead to a significant speed-up! In practice, b is typically chosen as b=8, 16 (byte, word), or even b=32 if the architecture supports it.

Although we have been mainly talking in terms of psuedo-code, we can look at the encode/decode times, thanks to implementations provided by Fabian Giesen.

# reading/writing one byte at a time

rANS encode:

9277880 clocks, 12.1 clocks/symbol (299.6MiB/s)

9276952 clocks, 12.1 clocks/symbol (299.7MiB/s)

...

rANS: 435113 bytes

14754012 clocks, 19.2 clocks/symbol (188.4MiB/s)

14723258 clocks, 19.2 clocks/symbol (188.8MiB/s)

...

decode ok!

# reading/writing 32 bits at a time:

rANS encode:

7726256 clocks, 10.1 clocks/symbol (359.8MiB/s)

7261792 clocks, 9.4 clocks/symbol (382.8MiB/s)

...

rANS: 435116 bytes

12159778 clocks, 15.8 clocks/symbol (228.6MiB/s)

12186790 clocks, 15.9 clocks/symbol (228.1MiB/s)

...

decode ok!

As you can see the speed up from going from b=8 to b=32 is quite significant! Note that getting such fast encoders/decoders is no mean feat. You should definitely take a look at the source code, to see how he implements this!

Vishnu: Wow, those numbers are quite incredible! I glanced through the github page, and noticed that these are some interlaced/SIMD rANS encoder/decoders there. What are these?

Brahma: Ahh! One thing you might note is that even though we have been able to significantly speed up the rANS encoders/decoders, they are still inherently sequential. This is a pity, considering the modern computer architectures have bumped up their compute through parallelization features such as: instruction level parallelism (ILP), multiple cores, SIMD cores (single instruction multiple data) and even GPUs. In a way, inspite of having SIMD cores, GPUs etc. our encoder is only currently using a core to run the encoder/decoder.

Any idea how we can parallelize our encoders/decoders?

Vishnu: Yes, I think we could cut the data into multiple chunks and encode/decode each chunk independently in parallel.

Brahma: Thats right Vishnu. Typically there are some threading overheads to doing things in this manner. One can however be a bit more smarter about it, and avoid any significant overheads. Fabian in his paper, explains how to achieve good performance with this parallelization, without incurring significant overheads. I myself have not read it yet, so would be great if either of you could do that for me!

What however struct me even more is that we can interleave two encoders/decoders together and eveen using a single core, thanks to instruction level parallelism, one can achieve some speed up. This is explained well in the blog and blog. We can also run the interleaved rANS variant, and compare the numbers for ourselves:

# rANS decoding

8421148 clocks, 11.0 clocks/symbol (330.1MiB/s)

8673588 clocks, 11.3 clocks/symbol (320.5MiB/s)

...

# interleaved rANS decoding

5912562 clocks, 7.7 clocks/symbol (470.2MB/s)

5775046 clocks, 7.5 clocks/symbol (481.4MB/s)

....

# interleaved SIMD rANS decoding:

3898854 clocks, 5.1 clocks/symbol (713.0MB/s)

3722360 clocks, 4.8 clocks/symbol (746.8MB/s)

...

Mahesh: Thanks Brahma for all the useful references! It is great to see the incredible speedups after system optimizations.

I am wondering if it is possible to take an entire different approach to speeding up the rANS encoding/decoding algorithms, which is caching. Considering our state is always limited to [L,H], in a way one can think of the encoding for example as a mapping from: [L,H] and the alphabet set to [L,H]. Thus, we just need to fill in these tables once and then it is just a matter of looking at the table for Would that work out?

# rANS encode_step function

encode_step(x, s) -> x_next, bits

## cached encoding:

# pre-process and cache the output of encode_step into a lookup table

encode_lookup_table[x, s] -> x_next, bits

Brahma: Good observation Mahesh! That is yet another way to speed up rANS, and is in fact a good segue to the tANS i.e. the table ANS variant. I will however leave the tANS discussion for some other day!

Table ANS (tANS)

Brahma: Even before we get started on caching our rANS encoder/decoders, lets take a minute to understand what is caching and what are the caveats which come with it.

Well, the idea of caching is quite simple: if there is some operation which you are doing repeatedly, you might as well just do it once as a part of pre-processing, (or even better during compile time) and then store this result in a lookup table. Now, when we need to perform this computation again, we can just look at our lookup table and retrieve the result. No need to repeat the computation!

This surely must be faster than doing the computation? Well, to answer this question, we need to ask another question:

How much time it takes to retrieve a value stored in a lookup table?

Unfortunately, the answer to this question is not as straightforward, due to the complex memory structure (for good reasons!) we have in modern computer architectures. But the thumb rule is that, if the lookup table is small, it is going to be fast, if it is large then it will probably not be worth it.

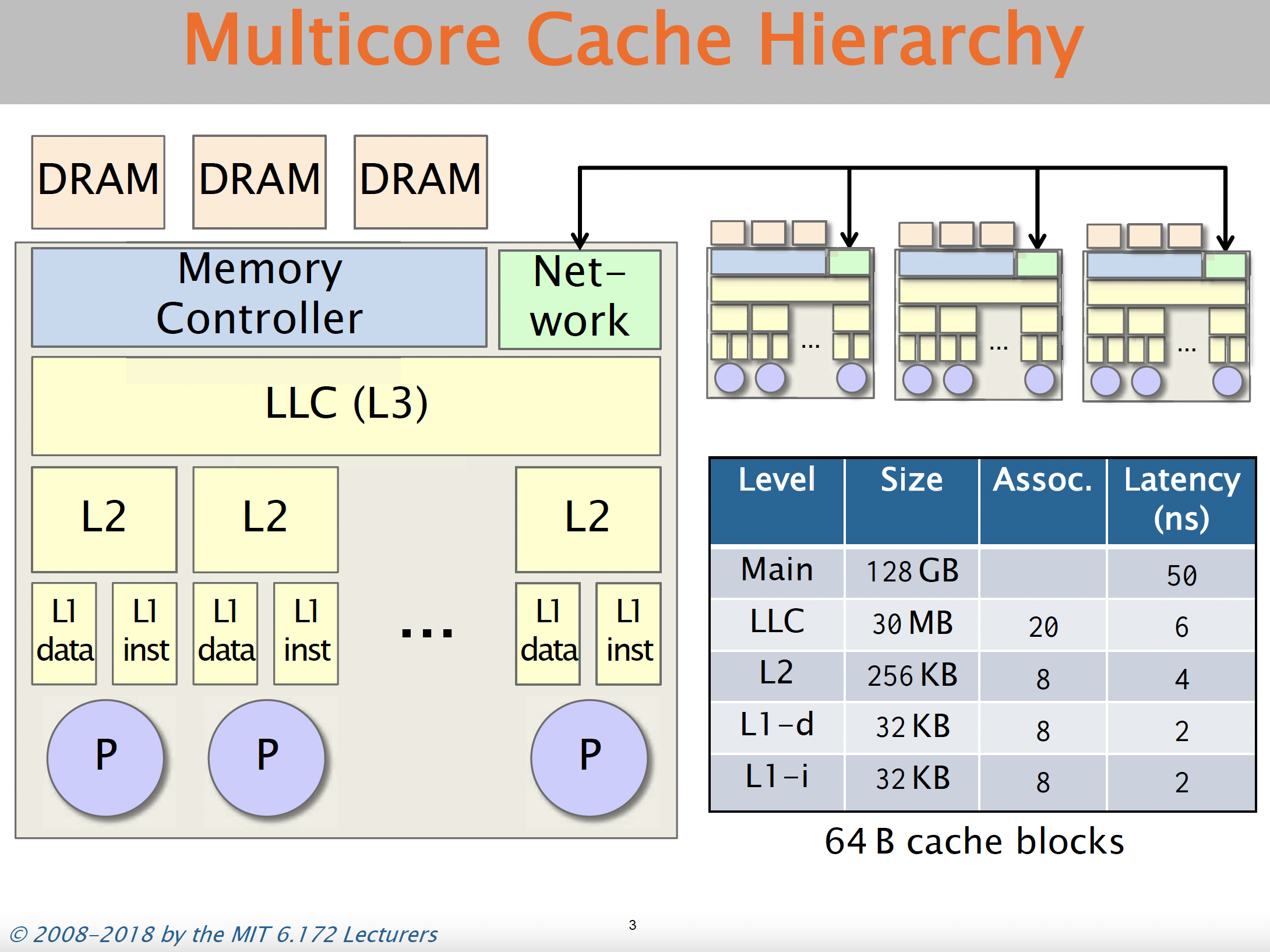

To be more specific: if the table is small (typically smaller than a few MBs) then it resides in the L1/L2 or L3 cache (also known as LLC -> Last Level cache). The L1/L2/L3 get progressively slower, but take about < 10 cycles which is quite fast. But, if your lookup table size is larger, then the lookup table resides on the RAM (i.e. the main memory), which is much slower with reading times ~100 cycles.

Here is a screenshot on the memory layout from the excellent MIT OCW lecture series

So, the thumb-rule we need to keep in mind while designing caching based methods is to keep the tables small. The larger the table, the more likely it is that we are going to get cache-misses (i.e. accessing data from the RAM), which is quite slow.

This thumb-rule should suffice for our discussion, but if you are interested in reading more on this, feel free to look at the following references:

- https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2002/07/caching/

- https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/6-172-performance-engineering-of-software-systems-fall-2018/

Brahma: Okay, now that we have a memory model as a reference, lets think about how we can go about caching rANS. For simplicity lets assume the following:

M = 2^r

L = M

H = 2M - 1

A -> alphabet size

i.e. we are choosing t=1 and M to be a power of 2. Lets try to think of what the decoding will look like first. Mahesh any thoughts?

Mahesh: Hmm, let me start by writing the decode_step function:

def decode_step(x, enc_bitarray):

# decode s, retrieve prev state

s, x_shrunk = rans_base_decode_step(x)

# expand back x_shrunk to lie in Interval[L,H]

x_prev, num_bits_step = expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray)

return s, x_prev, num_bits_step

I don't think there is a direct way to cache the entire decode_step function into a lookup table, as the enc_bitarray input is not finite in size, but we could probably cache the functions rans_base_decode_step and expand_state into individual lookup tables.

Let me start by thiking about rans_base_decode_step(x) first. This is just a mapping from x in [L,H] to x_shrunk, s. So the lookup table has M rows, each row consisting of the decoded symbol s and x_shrunk.

As for the expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray) function, it is a bit confusing as one of the inputs is enc_bitarray, so it is not obvious to me how to cache this function.

Brahma: Good start Mahesh! You are right that the expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray) in the current form is not amenable to caching. But, we can modify the expand_state function appropriately to make it cachable!

It is easiest to think about this in the binary alphabet.

Lets say r=5, i.e. M = 2^5, then

L = M = 100000b

H = 2L-1 = 111111b

and so the state x always looks like 1zzzzzb where z is any bit. Does this give any hints?

Vishnu: Ahh! I see, so after choosing M=2^r and looking in the binary alphabet, it is quite easy to imagine what expand_state is doing. For example: if x_shrunk = 101 then, the expanded state x will look like 101zzzb where z are the bits we read from the encoded bitstream.

Thus, we can simplify the expand_state function as:

M = 2^r

L = M

H = 2L - 1

####### Original expand_state func ############

def expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray):

# init

num_bits_step = 0

# read in bits to expand x_shrunk -> x

x = x_shrunk

while x not in Interval[L,H]:

x = x*b_factor + to_uint(enc_bitarray[num_bits_step:num_bits_step+b])

num_bits_step += b

return x, num_bits_step

######## New expand_state func #################

def expand_state(x_shrunk, enc_bitarray):

# if x_shrunk = 101, num_bits_step = (5+1) - 3

num_bits_step = (r+1) - ceil(log2(x_shrunk+1))

# get the new state:

x = (x_shrunk << num_bits_step) + to_uint(enc_bitarray[:num_bits_step])

return x, num_bits_step

Given the new expand_state function, we can convert it into a lookup table which outputs num_bits_step.

num_bits_step = expand_state_num_bits_table[x_shrunk]

As x_shrunk lies in Interval[freq[s], 2*freq[s] - 1], the expand_state_num_bits_table lookup table will at most have M rows.

Brahma: Great job Vishnu! That is indeed the correct way to go about things. Notice how our simplified expand_state function for M=2^r can also be used in non-cached rANS.

To summarise the here is how the new rans cached decoding will look like:

M = 2^r

L = M

H = 2L - 1

def rans_base_decode_step(x):

...

return (s,x_prev)

def get_expand_state_num_bits(x_shrunk):

# if x_shrunk = 101, num_bits_step = (5+1) - 3

num_bits_step = (r+1) - ceil(log2(x_shrunk+1))

return num_bits_step

### build the tables ###

# NOTE: this is a one time thing which can be done at the beginning of decoding

# or at compile time

# define the tables

rans_base_decode_table_s = {} # stores s

rans_base_decode_table_x_shrunk = {} # stores x_shrunk

expand_state_num_bits = {} # stores num_bits to read from bitstream

# fill the tables

for x in Interval[L,H]:

s, x_shrunk = rans_base_decode_step(x)

rans_base_decode_table_s[x] = s

rans_base_decode_table_x_shrunk[x] = x_shrunk

for s in Alphabet:

for x_shrunk in Interval[freq[s], 2*freq[s] - 1]:

expand_state_num_bits[x] = get_expand_state_num_bits(x_shrunk)

### the cached decode_step ########

def decode_step_cached(x, enc_bitarray):

# decode s, retrieve prev state

s = rans_base_decode_table_s[x]

x_shrunk = rans_base_decode_table_x_shrunk[x]

# expand back x_shrunk to lie in Interval[L,H]

num_bits_step = expand_state_num_bits[x_shrunk]

# get the new state:

x_prev = (x_shrunk << num_bits_step) + to_uint(enc_bitarray[:num_bits_step])

return s, x_prev, num_bits_step

That's it! this completes the cached rANS decoder. Let's also analyse how big our lookup tables are:

M = 2^r, L = M, H = 2L - 1

rans_base_decode_table_s #M rows, stores symbol s in Alphabet

rans_base_decode_table_x_shrunk #M rows, stores state x_shrunk <= H

expand_state_num_bits #M rows, stores num_bits (integer <= r)

So, the decoding lookup tables are reasonable in terms of size! for M = 2^16, the size of the table is ~200KB which is not bad!

Does that make sense?

Mahesh: Nice! Yes, it does make lot of sense. I believe the construction for L = M*t for a general t is also similar. We still need to assume M = 2^r for our caching to work I suppose.

Brahma: Thats right Mahesh! M=2^r does simplify things quite a bit. As we will see, it will also simplify the encode_step caching. Do you want to try caching the encoding?

Mahesh: Yes, let me take a stab: Lets start by writing the encode_step function structure again:

def encode_step(x,s):

# shrink state x before calling base encode

x_shrunk, out_bits = shrink_state(x, s)

# perform the base encoding step

x_next = rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s)

return x_next, out_bits

Lets start by looking at rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s) function first, We know that the input state x_shrunk lies in [freq[s], 2*freq[s] - 1]. Thus, we can replace rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s) with a lookup table:

base_encode_step_table = {} # contains the next state x_next

for s in Alphabet:

for x_shrunk in Interval[freq[s], 2*freq[s] - 1]:

base_encode_step_table[x_shrunk, s] = rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s)

The base_encode_step_table indexed by (x_shrunk, s) should contain in total sum(freq[s]) = M elements.

Now, coming to the shrink_state(x,s), I think it might again help visualizing the state x in the binary alphabet.

Lets again take the same example. Say r=5, i.e. M = 2^5, then

L = M = 100000b

H = 2L-1 = 111111b

and so the state x always looks like 1zzzzzb where z is any bit. If you recall, the shrink_state function basically streams out the lower bits of the state x, until it is in the Interval[freq[s], 2*freq[s] - 1].

Now, lets say, freq[s] <= 2^y < (2*freq[s] - 1). Then we know the following:

- For any

x_shrunk in [2^y, 2*2^y - 1], we need to outputr+1-ybits. - For any

x_shrunk in [2^{y-1}, 2*2^{y-1} - 1], we need to outputr+2-ybits.

Note that there can be one and only one integer y satisfying the condition. Also, note that due to the size of the interval [Freq[s], 2*freq[s] - 1], we either output r+1-y or r+2-y bits, no other scenario can occur. This should help us simplify the shrink_state function as follows:

M = 2^r

L = M

H = 2L - 1

####### Original shrink_state func ############

def shrink_state(x,s):

# initialize the output bitarray

out_bits = BitArray()

# shrink state until we are sure the encoded state will lie in the correct interval

x_shrunk = x

while x_shrunk not in Interval[freq[s]*t,2*freq[s]*t - 1]:

out_bits.prepend(x%2)

x = x//2

return x_shrunk, out_bits

####### New/Simplified shrink_state func ############

def shrink_state(x,s):

# calculate the power of 2 lying in [freq[s], 2freq[s] - 1]

y = ceil(log2(freq[s]))

num_out_bits = r+1 - y

thresh = freq[s] << (num_out_bits+1)

if x >= thresh:

num_out_bits += 1

x_shrunk = x >> num_out_bits

out_bits = to_binary(x)[-num_out_bits:]

return x_shrunk, out_bits

The new shrink_state much more amenable to caching. We can just cache the y, thresh values for each symbol s. This completes the encode_step caching. The full pseudo-code is as follows:

M = 2^r

L = M

H = 2L - 1

def rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s):

...

return x_next

def shrink_state_num_out_bits_base(s):

# calculate the power of 2 lying in [freq[s], 2freq[s] - 1]

y = ceil(log2(freq[s]))

return r + 1 - y

### build the tables ###

# NOTE: this is a one time thing which can be done at the beginning of encoding

# or at compile time

base_encode_step_table = {} #M rows, each storing x_next in [L,H]

for s in Alphabet:

for x_shrunk in Interval[freq[s], 2*freq[s] - 1]:

base_encode_step_table[x_shrunk, s] = rans_base_encode_step(x_shrunk,s)

shrink_state_num_out_bits_base = {} #stores the exponent y values as described above

shrink_state_thresh = {} # stores the thresh values

for s in Alphabet:

shrink_state_num_out_bits_base[s] = shrink_state_num_out_bits_base(s)

shrink_state_thresh[s] = freq[s] << (shrink_state_num_out_bits_base[s] + 1)

### the cached encode_step ########

def encode_step_cached(x,s):

# shrink state x before calling base encode

num_out_bits = shrink_state_num_out_bits_base[s]

if x >= shrink_state_thresh[y]:

num_out_bits += 1

x_shrunk = x >> num_out_bits

out_bits = to_binary(x)[-num_out_bits:]

# perform the base encoding step

x_next = base_encode_step_table[x_shrunk,s]

return x_next, out_bits

Brahma: Very good Mahesh! That is quite precise. Lets again take a minute to see how much memory do our encoding lookup tables take:

M = 2^r, L = M, H = 2L - 1

base_encode_step_table = {} #M rows, each storing x_next in [L,H]

shrink_state_num_out_bits_base = {} # A rows (alphabet size) each storing the base num_bits <= r

shrink_state_thresh = {} # A rows (alphabet size) storing an integer <= H

For an alphabet size of 256, this takes around 100KB which is quite reasonable. Note that the cached version of the encoding is a bit slow as compared with the decoding, as we need to do a comparison, but it is not bad at all.

Vishnu: Thanks Brahma! Is the cached rANS another name for tANS or the table ANS? Intuitively the name makes sense, considering all we are now during encoding and decoding is access the lookup tables!

Brahma: You are right Vishnu! In fact cached rANS, the way in we have discussed is in fact on variant of the table ANS, the tANS. So, in a way tANS is a family of table-based encoders/decoders which have the exact same decode_step_cached and encode_step_cached functions. The main difference between them is how the lookup tables are filled.

For example, if you look at the lookup tables we have, the only constraint we have for the encode table base_encode_step_table and the decode tables rans_base_decode_table_s, rans_base_decode_table_x_shrunk is that they need to be inverses of each other.

base_encode_step_table[x_shrunk, s] = x

# implies that

s = rans_base_decode_table_s[x]

x_shrunk = rans_base_decode_table_x_shrunk[x]

We can for example, permute the values in the tables, ensuring that they are inverses, and that will give us another tANS encoder/decoder.

Vishnu: Is there a particular permutation of these tables which is the optimal tANS?

Brahma: As you can imagine, all of these tANS encoders have subtle differences in their compression performance. A more in-depth analysis on tANS and which permutations should one choose is discussed in great detail by Yann and Charles:

This brings us to the end of our discussion on the Asymmetric Numeral Systems. Hope you enjoyed the discussion! In case you are interested in learning more, here is a curated list of references

- Original Paper: Although the algorithms are great, I unfortunately found it difficult to follow the paper. Still, it might be good to skim through it, as everything we discussed is in there (in some form)

- Fabian Giesen's Blog: Great blog + implementation focused on

rANS. the seqeunce of articles also illustrates some brilliant tricks in code speed optimizations to makerANSfast. - Charles Bloom's Blog: Great sequence of articles again. We borrow quite a few things (including the examples) from here. It contains more in-depth discussion of different variants

tANSamong other things - Yann Collet's Blog: A sequence of articles discussing

tANSfrom a totally different perspective, which connectstANSwith Huffman coding and unifies them under a single framework. Very illuminating!

TODO: Add links to theoretical works on ANS